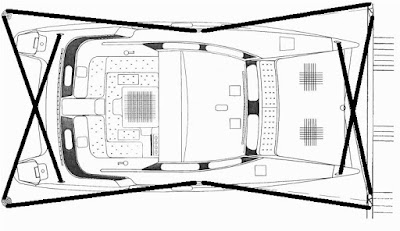

As I begin work on a mooring project (related to anchoring--it seems easier to the sailor, maybe, but it's longer term and the boat is unsupervised), I consider what is work teaching. It's easy to point at bad knots--and I will do that--but serious failings are often more subtle. Take these owner's manual drawings for the PDQ 32:

Note: I have BOLDED the lines in each case to draw the eye to the triangular patterns. Perhaps it makes it easier to visualize the load sharing.

Between Pilings. Very conventional, but still there are obvious failings. All of the lines should be nylon, roughly the same size. Some authorities suggest that the springs can be lighter, based I suppose on the fact that the bow-wind and stern-wind loads are lighter. However, in the event of a breast line failure, you'll wish they were full strength.

- The bows are too close to the dock. There will certainly be slack, to allow for tide and wakes, and this boat will hit.

- The slip is too small. I'll assume this was illustrator license, but clearly the stern piling are a problem.

- The bow line and stern line angles are too perpendicular tot he boat. They would take some strain off the springs if the angle were less. Additionally, the boat would be safer if any one line broke.

- Where does the dingy go (the lines are going right through it)? The answer on the PDQ is to add deflectors down low, inside the stern, to run the lines under the dingy.

There are also many positives. A lot of redundancy, more than seems obvious.

- Greatly reduced motion and loads. I'm waiting on windy weather to take load readings both with and without the springs.

- If any one lines break, the boat is still well controlled, depending on slack.

- With any 2 lines broken, even next to each other, the boat will not hit anything, if the slip is properly sized. I've tested this both with models and full scale.

- With any three lines broken it may rub on one piing, but will not go far enough into the next slip to strike another boat. With good rub rails, you are probably OK.

Alongside. Also conventional, with some of the same failings.

- Where does the dingy go? Same solution.

- No fender boards. While not needed on floating docks, they are mandatory if tied beside pilings.

- Bow an stern line angles should be greater, in case the spring fails.

- I believe the springs (alongside only) should be polyester. There is no need to absorb shock and the main purpose of the spring is to keep the boat positioned properly for the fenders to match pilings. Even with fender boards, sliding fore and aft is asking for trouble. As it is, the boat will still move fore-aft a foot or two with the tide, since the spring will describe an arc of a circle, where the radius is the half length.

The bad thing is that a single failure will move the boat enough to pop a fender out. What Would I do for storms?

- 2 fender boards. for pilings, lots of fenders for floating docks.

- Additional springs. Either from the bow and stern forward and aft, or if length does not permit, from the mid-point of the dock to the bow and stern cleats.

- Additional breast lines But I would not change the angle much; An angles breast line increases the pressure on the fenders in an end wind.

But mostly, this is a good plan. There are no short lines, so shock and tide are attenuated. No single failure is fatal (assuming the slip is a little bigger).

----

This advise from West Marine, is just lame:

- The power boat should have springs to both sides.

- The stern lines should be crossed

- The Sailboat should NOT have a spring line anchored to the chain plate or the winch!

- The breast lines should be perbendicular to the dock (less leverage on the fenders.

In other words, not much is right. I sure hope it is a floating dock, but even so....